- Home

- Laura Buzo

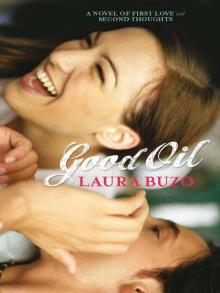

Good Oil

Good Oil Read online

Good Oil

Good Oil

Laura Buzo

This project has been assisted by the Australian Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body.

First published in 2010

Copyright © Laura Buzo, 2010

Extracts © Kate Jennings. Reproduced by kind permission of the author.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or ten per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Fax: (61 2) 9906 2218

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

Cataloguing-in-Publication details are available from the National Library of Australian www.librariesaustralia.nla.gov.au

ISBN 978 1 74175 997 6

Cover and text design by Zoë Sadokierski

Cover photo by Getty Images

Set in 12.5 pt Perpetua by Midland Typesetters, Australia

Printed in Australia by McPherson’s Printing Group

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To absent friends

Contents

Spheres of No Influence

The Purple Note Book

Smoke and Mirrors

The Black Note Book

Clear Water

About the Author

Acknowledgements

Spheres of

No Influence

LIGHTS UP

‘I’m writing a play,’ says Chris, leaning over the counter of my cash register. ‘It’s called Death of a Customer. Needless to say, it’s set here.’ He jerks his head towards the aisles lined with groceries and lit with harsh fluorescent bars.

It takes me a moment to place the reference, but then I remember Death of a Salesman from when Dad took me to see the play last year.

‘Sounds good.’

‘Want to be in it?’

I nod eagerly.

‘Cool. We’re going to the pub after work to workshop it.You should come.’

‘Who—’ I squeak. ‘Who’s going?’

‘Oh, Ed, Bianca, Donna . . . people.’

I am only three weeks past my fifteenth birthday, but my braces came off a month ago so I could possibly slip in to a pub looks-wise. Trouble is, my scorching unease would give me away to the door guy, and even if by some miracle it didn’t, I am terrified of interacting socially with my workmates. Except Chris.

Donna is my age, but she has no trouble keeping up with them. She wears eye make-up and pulls it off. She wears calf-high black boots with purple laces. She smokes and has been kicked out of home by her father several times. She has serious street cred. Unlike me. Ed is nice enough but he’s eighteen and kind of vagued-out all the time. Bianca is twenty-three and ignores me so consistently that it must be deliberate. I am not going to the pub with them.

‘I can’t,’ I say.

‘Why not?’

‘I have homework.’

This is not a lie. I’m struggling in maths as it is. Getting behind will make it worse. My shift ends at nine o’clock, so even if I go straight home I won’t get to my homework until nine forty at least.

Chris’s face contracts in annoyance. ‘So? I have a 2000 word tute paper due on Friday. Life must still be lived.’

‘I can’t.’

‘You can do it in the morning.’

I shake my head.

‘I’ll take you home afterwards. You’ll be home by midnight.’

Now I’m torn. Two hours of sharing him with the others and then I’d be rewarded by fifteen minutes of having him all to myself on the walk home.

‘Ed’s got his parents’ car tonight. We’ll drop you right at your door.’

Crap. ‘I can’t.

‘Fine, whatever,’ he says, withdrawing his presence like a parent confiscating a favourite toy. He stalks off in the direction of the deli, probably to ask ‘she’s-big-she’s-blonde-she-works-in-the-deli’ Georgia to go to the pub and join the collaboration on his dramatic masterpiece.

As Chris’s name for her suggests, Georgia is in fact blonde, has big breasts and manages to wear the deli’s white tunic uniform in a way that is quite fetching. However, my point of envy is the fact that, at eighteen, she is a good three years closer in age to Chris.

‘No fair,’ I mutter as he disappears from sight.

LAND OF DREAMS

Chris never refers to the Woolworths we work at as Woolworths. He calls it the Land of Dreams. On nights and weekends, the Land of Dreams is staffed by casuals. Mainly high-school students (me, Street-cred Donna and several others who go to public schools in the area), university students (Chris, Kathy, Celene, Stuart) and a few other ‘young adult’ types who obviously haven’t yet decided what to ‘do’ with their lives and are working at Woolies while they figure it out (Ed, Bianca, Andy).

Come to think of it, that may be a bit of an assumption on my part. I’ve never actually seen Ed, Bianca or Andy grappling with the mystery of their existence or their place in the universe. They’re just there. Ed to earn enough money to support his pot habit, Bianca to flirt with the teenage checkout boys. And Andy? Well, who knows; he rarely says anything.

I started work at the Land of Dreams last year, almost on the dot of age fourteen and nine months. This was a move motivated by a passionate aversion to asking my parents for money, and the knowledge that there was not much of it going spare around our way in any case. Money is never openly discussed in my house, but I suspect that last year was a bit tough. My sister Liza moved out to go to university in Bathurst, and my dad was longer than usual between jobs. Asking for money began to stress me out. Dad would say he didn’t have any cash and to ask Mum. Mum would sigh and look pissed off and give it to me with less than good grace. So I thought, Enough of that.

I went to the local shopping centre and asked for work at every shop except the butcher (eww) and the tobacconist (evil). I really had to push myself to go in each time and not stumble over my words. I did stumble at a few of them, but most took my details and said they’d call if something came up. One week later a lady from Woolworths rang and asked me to come in for an interview after school. I started a week after that.

The morning of my first training shift I came down to breakfast. Dad was reading the newspaper and Mum was wiping up some Milo spilt on the floor by my little sister.

‘I’ve got a job at Woolworths,’ I said.

‘At Metro Fair,’ I added.

‘On the checkout,’ I concluded.

Mum nodded as she wiped.

‘Good,’ said Dad, looking up from his newspaper for a second. ‘That’s good, darling.’

Ever since then I’ve been working three nights a week from 4 p.m. till 9 p.m., and from 12 p.m. till 4 p.m. on Saturday or sometimes Sunday.

I’ve got my work routine down pat. At the final school bell I make my way to my locker amid hordes of girls stampeding to freedom. My locker is next to my best friend Penny’s locker, so we always meet at the end of the day. I change out of my school tunic and shoes and into my black work pants and black shoes.

‘Sweetie-pie,’ Penny often says, watching me struggle into my work pants and hoick my tunic over my head

trying not to take my shirt up with it. ‘There’s got to be an easier way.’

She holds the shirt down for me and catches me if I lose my balance while unknotting the laces of my school shoes. I stuff my school uniform into my backpack and gather up my textbooks and folders. Then we join the throng and negotiate our way outside.

As Australia is ‘girt by sea’, my school is ‘girt by road’. Major, six-lane traffic arteries on all sides. Heavy on the fumes. When it rains, great swathes of dirty, oily water collect in the gutters. Then buses roar past and send litres of energetic spray up onto the pavement. In the five metres between the kerb and the school fence there’s no escape. It’s bad enough if you get drenched while waiting for the bus home, but getting caught on the way to the school gates in the morning seriously blows.

My afternoon bus is the 760. I never get a seat as the boys from the brother school next door are ferocious pushers. Some of my most disillusioning school moments have involved getting stuck in a crush with twenty or so teenage boys who have no qualms whatsoever about going straight over the top of anyone smaller or less inclined to push. They shove, swear, show off and certainly aren’t above hair-pulling. Vindication sometimes comes with a certain bus driver who won’t let any of the boys on until all the girls are aboard. The boys jeer under their breath as we girls file on, and you can bet they’re even more merciless the next day.

Most days I’m happy to hang back and see if I can squeeze on at the end. But on Woolies days, I have to get on or I’ll be late for work. The 760 gets me to Woolies by 4 p.m., whereupon I don my red scarf and name badge, shove my stuff into my locker, check the roster to see what register I’m on that shift and jump on.

THE ROPES

‘Miss Amelia Hayes, welcome to the Land of Dreams!’

The boy grinned at me and motioned me into the same tiny room I’d been interviewed in.

‘I’ll leave you to it then,’ said the manager, and she closed the door.

The boy and I regarded each other for a moment. I judged him to be about twenty. His features were unremarkable, but his face was open, immediately warm and engaging; he seemed to twinkle.

‘I,’ he said, ‘am Chris, your friendly staff trainer.You’ll be with me for three four-hour shifts. I will call you grasshopper and you will call me sensei, and I will give you the good oil. Right?’

‘Okay.’ I smiled. It was hard not to.

‘Now,’ he said, fumbling in his pants pocket. ‘Where’s your . . . ? Got it.’ He pulled out a name badge that said Trainee. ‘This baby is yours for three days, and after that, if you play your cards right, you’ll get your very own to love and cherish for all your days.’

He approached me and fastened it to my shirt. I wasn’t sure where to look.

‘Just so you know, I’m open to all kinds of bribery.’

‘Good to know.’

‘Now, let’s get out there.’

Chris taught me how to pack groceries in such a way as to incur the overall least amount of wrath from the customer. However, he stressed, you can’t please everyone. He taught me about the more obscure fruit and vegetables: swedes, rambutan, jackfruit, persimmon, durian, tamarillo, dragon fruit, star fruit, okra. And the many different kinds of apple: fuji, Braeburn, pink lady, bonza, jonathon, Sundowner, Red Delicious, Golden Delicious, Granny Smith. Then there were brushed potatoes, washed potatoes, desiree potatoes, new potatoes, kipfler potatoes and pontiac potatoes. At the beginning, he said, I would have to look up the different codes for each of them, which would be tedious and slow, but soon enough they would all be in my head.

Chris also told me that every so often I would have a complete jerk come through my register.

‘The important thing to remember,’ said Chris, ‘is It’s Not About You. Some people are just pricks. And that’s not only true in here.’

On the third night of training it was time for me to serve my first customers. Chris stayed beside me for the first few and then hovered close by for an hour, twinkling encouragement and appearing at my side if I was struggling with anything. At about eight o’clock the rush had finished and he sidled over.

‘I think you’ve earned a break, youngster.’ He smiled and put up the closed sign on my register. ‘I’ll buy you a Coke.’

We sat drinking our Cokes in the deserted food hall of the shopping centre. All the shops were in darkness with their security shutters down.

‘So, Amelia, how old would you be?’

‘I’m fifteen. Almost.’

‘Wow, you really are a youngster.’

‘Guess so.’

‘You like school?’

‘Yeah. Yeah, I like it most of the time. Not maths though.’

‘The best thing about finishing school is not having to do maths anymore.You mark my words.’

‘Can’t wait.’

‘Favourite subject?’

‘English. Definitely. My teacher this year is a bit weird, but still . . .’

‘Your love is strong and true.’

I looked at him. ‘What?’

‘For English.’

‘Oh, yeah. For sure. I just hope I don’t get her for senior English.’

‘Got someone else in mind?’

‘Miss McFadden. Everyone wants Miss McFadden.’

‘But they can’t all have her.’

‘No, they can’t.’

It’s really easy to talk to him, I thought.

‘What about you?’ I asked.

‘Me. I’m in my last year of Arts at New South.’

‘What do you take?’

‘Double major in English and sociology. Honours in sociology next year.’

‘Then what?’

‘Oh, don’t you start,’ he said sharply.

Chastened, I drank my Coke.

‘Got brothers or sisters?’ he asked.

‘Older sister, Liza. She’s away at uni. Charles Sturt. Lives in Bathurst in some share-house.’

‘Half her luck.’ He grimaced. ‘I’m with the folks.’

‘You don’t get on?’

‘They’re nice people. It’s not bad. It’s just . . . It’s gone on too long. But there’s no other choice. So . . .’ he trailed off.

‘And my other sister has just turned three.’

‘Three! Wow.’

‘I know.’

‘Contraception doesn’t work in the top drawer.’

‘They know that now.’

We laughed.

‘She’s super-gorgeous though,’ I said, my heart swelling a little at the thought of Jessica’s soft chubby cheeks and philosophical musings. That morning she had approached me while I ate my toast. Amelia. She laid one of her hands gently over mine. My hands don’t come off. They’re attached to my body. So true.

‘Got a boyfriend?’

‘What? No. How would that even happen?’

I hadn’t really talked to a boy since primary school. My only male contact was with the pushers and shovers on the bus, and they fell short of every expectation. Talking to them wouldn’t be like this, I thought.

‘Got a girlfriend?’ I countered.

He twisted the ring-top on his Coke can and then pulled it off. ‘No.’ He threw the can in the direction of a bin a few metres away. It missed, clanged against the metal and hit the ground.

‘We’d better get back in there.’

I nodded and pushed back my chair.

‘Oh, and you should join the union, youngster. It doesn’t cost much and by God you’ll get screwed around here.’

The weeks went on and I settled into the routine of going to work after school. It was a little harder to keep up with school work, but nothing that couldn’t be remedied by late-night caffeine hits and working through the odd lunch period. Chris often brought drafts of his uni essays in to work for me to read during my breaks. His favourite course was The History of Popular Culture. His essays were littered with references to his favourite films, which I soon learned were along the lines of Alien,

Rambo, Platoon, Apocalypse Now and The Godfather. So different to what we were studying at school. He asked me what I thought of his work and he listened to my replies.

‘So, youngster,’ he said one day, fixing me with an eagle eye. ‘Why did Barnes shoot Elias?’

‘Why did— Who?’

‘Barnes! He shot Elias. Why?’

‘I don’t know what you’re—’ ‘Don’t – do not tell me you haven’t seen Platoon.’

I obliged, and remained silent.

‘What do they teach you at that school?’

Another day, in line to pick up our pay slips at the back office: ‘So the mothership in Alien clearly draws on feminist theory don’tcha think?’

I don’t watch scary movies. I mean it. Not ever. They make me scared. Scared of being alone in the house. Scared of being alone upstairs at night. Scared of walking home from work in the dark. Penny can watch scary movies and be completely unaffected. She can watch The Silence of the Lambs in bed and then fall sweetly asleep. I didn’t sleep for a week after we watched it last year. Never again.

‘It’s not horror, youngster; it’s science fiction. Trailblazing science fiction.’

Each conversation with Chris seemed to prompt an exhausting mix of excitement and forehead-slapping embarrassment at my inability to keep up with the references and in-jokes. Real or perceived. I go to an all-girls school where people are bent on studying. I wasn’t used to talking to boys at all, let alone grown-up ones with university essays to write and incredible charisma. So, so far out of my depth.

SUMMER

I worked Christmas Eve, as did Chris and most of the other casuals. He finished his shift an hour before me and spent a good half-hour doing his man-about-Woolworths routine: entertaining the girls; engaging in serious-looking talks with the managers, his arms crossed, nodding with a furrowed brow; counselling Ed at the service desk about his life choices, or lack thereof. It was amazing how he was able to talk to anyone and everyone with confidence. I wasn’t the only one who revelled in the easiness of talking to Chris. Everyone had a better shift when Chris was on.

Love and Other Perishable Items

Love and Other Perishable Items Good Oil

Good Oil